* Another story from the archive this week, an autumnal walking piece with a pilgrimage theme.

Follow me on Twitter or subscribe to the RSS for more story updates.

Werburgh looks down serenely from the east window of Chester Cathedral’s Refectory.

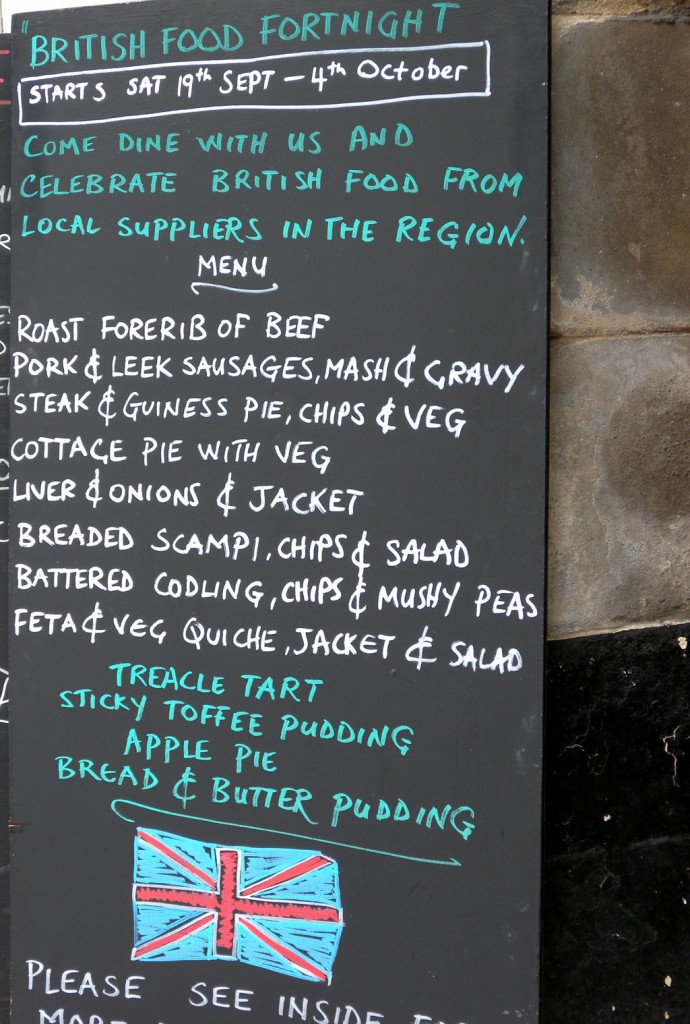

The room is a chaos of school groups, small children and international visitors, all tucking into Welsh rarebit and baked potatoes. But Chester’s Patron Saint, her hand grasping the staff of an abbess and a model of the monastery founded on this site in the other, is the epitome of saintly calm.

The elaborate stained-glass window, based on the writings of the monk Henry Bradshaw at the Abbey of St Werburgh in 1513, celebrates her saintly life and eternal connection to Chester.

Werburgh, known as St Werburga in Old English, may be less famous than St Cuthbert or St Aidan, but she remains a constant calming presence in Roman city of Chester.

This month her presence will be felt her even more keenly. The Cathedral will celebrate her feast day on February 3 with a special service, while the journey of Werburgh from a noble Staffordshire family to sainthood provides the narrative backdrop to the Two Saints Way, a newly opened long-distance walking trail through the rural heart of England.

Walk the trail in the winter months to have the sun behind you and catch the best views.

Walking trail

The trail divides into four sections over, typically, seven days and recreates the ancient pilgrimage route between Lichfield and Chester Cathedrals via Stafford and Stoke-on-Trent.

The trail’s name refers to St Werburgh and St Chad, two Saxon saints who brought Christianity to the ancient kingdom of Mercia (the modern-day Midlands) in the 7th century. The saints were laid to rest at Chester and Lichfield respectively, their relics fuelling the rise of medieval pilgrimage routes across the British Isles onto Rome or Jerusalem.

Some followers went on pilgrimage to seek spiritual healing as miracles were reported to have happened in the places where the saints were buried – Chester claims two, whereby parading her bones around the city walls saved the city from disaster.

Others were dispatched to atone for their sins. Indeed, church records from the village of Tarvin, just outside Chester, show some sinners were sent on the pilgrimage to Lichfield for the crime of fornification.

The heyday of pilgrimage declined with the Act of Supremacy in 1534, installing Henry VIII as head of the Church of England, but these trails are increasingly popular again today with latter-day pilgrims seeking spiritual connections on a long-distance hike.

“The pilgrimage has become a contemporary quest for ancient wisdom. It encapsulates what life is about, namely going on a journey,” says David Pott, who devised the Two Saints Way and is walking with me on the trail.

“In the contemporary context, it’s about asking questions and seeking answers. But modern pilgrims seek to do so in mind, body and soul.”

Country paths

I set out to explore a section of the trail closely associated with Werburgh, making my base at the medieval pilgrimage town of Stone in rural Staffordshire.

The nine-mile day walk leads from just south of Stone to the Trentham Estate near Stoke-on-Trent. Pilgrims can also walk the 88-mile route as a complete linear trail from Lichfield to Chester, the path waymarked with the symbol of the goose, a reference to one of Werburgh’s miracles.

There are less written of Werburgh’s journey and fewer tangible sites linked to her than Chad. The main source of reference is a document written by the Flemish monk Goscelin in Canterbury in the late 10th century.

However, ecclesiastical records do record something of her life. Werburgh, the daughter of the Mercian King Wulphere, attracted many admirers but devoted herself to God. She defied her father’s command to marry and instead entered the Abbey of Ely, falling to her knees upon arrival to remove her regal garments and exchange them for the nun’s habit.

Werburgh went on to found convents in Northamptonshire, Staffordshire and Lincolnshire. She was buried at Hanbury, but her body was later moved to Chester.

On a bright but crisp winter morning, I join the trail at the village of Burston, some 30 miles north of Lichfield. My path hugs the Trent and Mersey Canal for the first couple of miles, skirting the village millpond and the old pilgrimage church of St Rufin.

I then follow a public footpath beside a gurgling brook towards Stone, crossing a Wildlife Trust site alive with birdlife and occasional sightings of otters.

The trail leads down the High Street in Stone, past iron railings recounting the story of Wulphere, to Stone Priory and the church of St Mary and St Wulfad [pictured above], the latter one of Werburgh two brothers martyred by their own father. The original Augustinian Priory on the site on the site dates from the 12th century while the present Gothic-style church was built in 1758.

Victorian stained glass windows on the north aisle depict Chad, Werburgh and her brothers. The seal of Stone Priory was found in a field in 2011 and returned to Stone later that same year. The 13th-century copper-cast seal depicts St Mary with, some suggest, St Wulfad, sat beside her.

During the next section, leaving Stone for the village of Tittensor, recorded in the Doomsday Book of 1086 as Titesovere, and then onto Trentham, the trail opens up to reveal more open farmland and woodland.

Tucked behind a wooded hill is Bury Bank, an ancient hill fort formerly known as Wulphercestre (Wulphere’s camp), probably the capital of the ancient kingdom of Mercia. This site is believed to be Werburgh’s birthplace, while Saxon’s Lowe, just beyond the fields along a path known as Nun’s Way, is an Iron Age burial place.

Wulphere is believed to have chosen this ancient site as his burial place before his death in 675AD.

I complete the day’s walking, traversing the 300-year-old woodland of the Trentham Estate, to finish with a moment of contemplation at St Mary’s Church, Trentham. The praying stone, lying before a Saxon cross in the churchyard, has been smoothed over during centuries by the knees of travellers gathered in prayer.

Cathedral quarter

The next day in Chester, having skipped over a section through rural Cheshire, Nick Fry, Heritage, Visitors and Exhibition Manager at Chester Cathedral, is showing me around the cathedral’s signposts to the Werburgh story.

We start at the Quire, the place where the monks would pray, and identify the misericord, one of Chester Cathedral’s little known treasures. The carved seat for monks is engraved with scenes from Werburgh’s life. “It’s like a medieval cartoon strip dating from 1380,” smiles Nick.

The Cathedral has been a place of pilgrimage since 907AD when the first stone church was built in Chester to hold Werburgh’s relics. Her effigy still fills the cathedral today, the St Werburgh Pilgrimage Trail leading from the Refectory via the Quire to the Lady Chapel, home to the shrine of St Werburgh.

After a life of religious devotion, Werburgh died around 700 and her body was moved to Chester from Hanbury in 875 to protect it from waves of Viking raiders attacking England. The cult of Werburgh survived centuries of conquests and, in the 14th century, an elaborate shrine was built in her honour with 34 carved figures and a number of niches where pilgrims could kneel in prayer before the saint.

Henry VIII commanded the shrine be broken into fragments during the dissolution of the monasteries in the 16th century and it wasn’t until 1876 that A.W. Blomfield, charged with restoring Chester Cathedral, collected the fragments. The Lady Chapel is today a popular place for pilgrimage and prayer at the cathedral.

Nick says, as we stand before the shrine, contemplating a small carved effigy of Werburgh below where the casket of her relics would have been stored:

“Pilgrims still come here as they did in the Middle Ages. They still want that feeling of wholeness, both physical and spiritual.”

In medieval times, pilgrims believed in the healing power of the saints and the way their powers infused the stone of the shrine, hence they wanted to get as close to her, and pray to her, for as long as possible. There would have been scenes of jostling. These so-called squeezing spaces, where pilgrims would bask in her presence, are still visible around the base of the shrine.

“We still sometimes find little posies of flowers around the base,” says Nick as the presence of the ancient saint engulfs us. “Werburgh is a calming influence,” nods Nick.

“There’s something about being here that just brings a sense of quiet to us all.”

* This story was first published in Discover Britain magazine in 2012. Liked this? Try Pilgrimage Trails on the Llyn Peninsula.

And post your comments below.