He was a four-time British prime minister and dominant figure of the Victorian era.

Clashing regularly in Parliament with his arch-rival Disraeli, he was described by Queen Victoria as a “half-mad firebrand”.

But a weekend visit to his ancestral estate in North Wales reveals his lesser-known passions for literature and collecting axes.

Away from Parliament, it seems, William Ewart Gladstone was a voracious reader and loved nothing more than chopping wood in the grounds of his stately pile.

Modern artworks

A new holiday let on his family estate in the village of Hawarden, located near the Chester border, draws back the curtain on the starched image of one of our greatest statesmen.

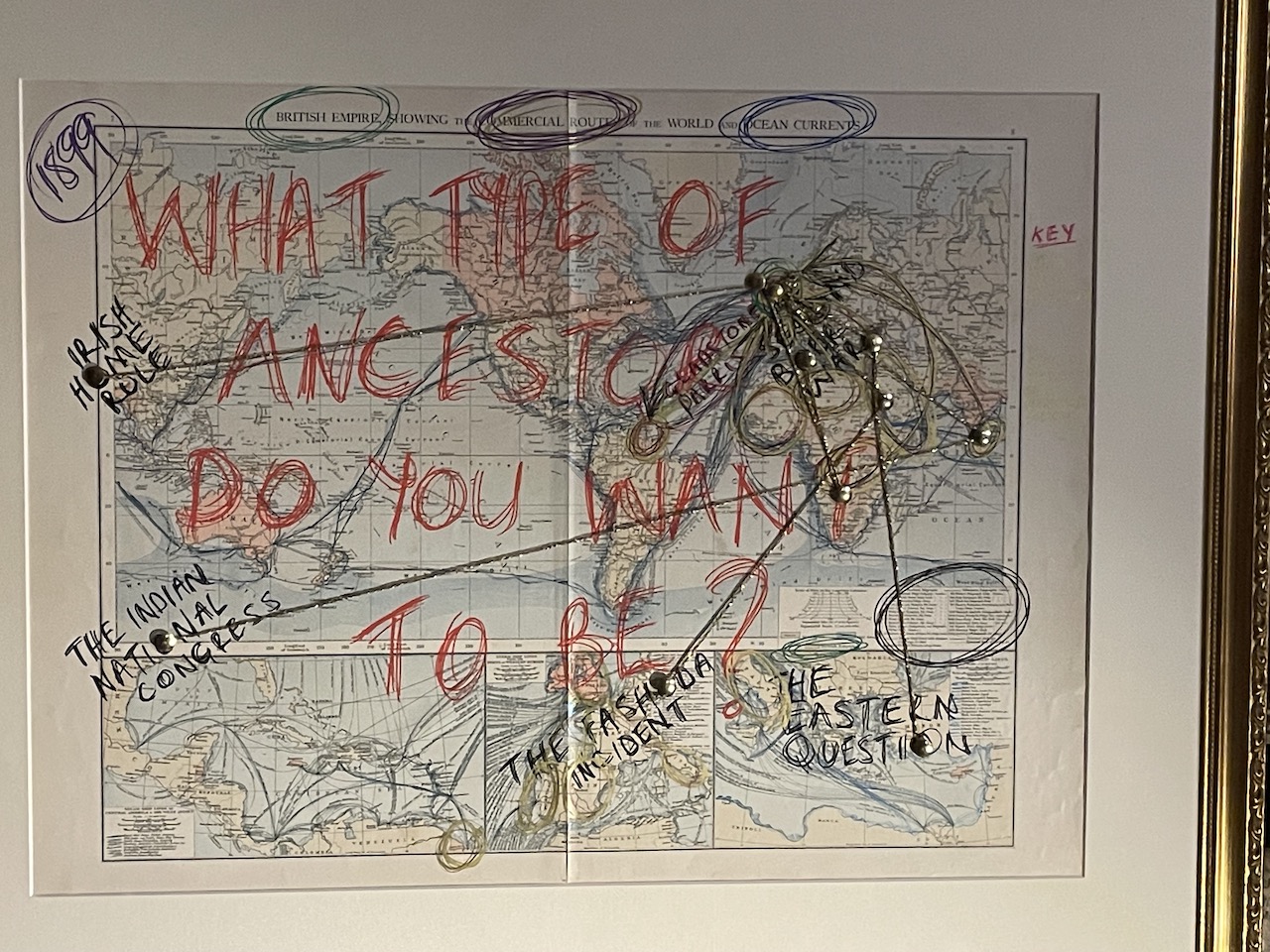

The West End, located within the western wing of 19th-century Hawarden Castle, has five stylish bedrooms and grand communal areas, blending the modernity of Yoko Ono and Damian Hirst artworks with Georgian-era furniture.

The meticulous home-from-home touches, such as Max Richter albums and coffee-table tomes about David Hockney and Johnny Marr’s guitars, have been curated by Charlie Gladstone, the great-great grandson of the Liverpool-born former PM, whose family still lives in the adjoining house.

Guests have exclusive access to the time-capsule Temple of Peace, Gladstone’s private library, and bespoke experiences, such as dinner cooked by the estate’s head chef, or a yoga session in the sprawling grounds.

A private woodland glade comes with an al-fresco wood-fired oven and hot tub.

After settling into our rural retreat with a hamper of goodies from the nearby Hawarden Estate Farm Shop, we set out against a wintery landscape to explore the walking trails, leading through the estate grounds to the village.

We pass the Walled Garden School with its regular programme of talks and classes, a group absorbed in Indian Head Massage as we stroll by, then emerge into a thriving rural village.

It boasts a clutch of restored estate cottages, a village store and a cosy local pub, the Glynne Arms, for pints of local ale and a slap-up supper of fish pie and sticky toffee pudding.

A pair of axes glimmer above the open hearth, a reminder that everything in Hawarden nods to Gladstone’s legacy.

“We think of him as rather rigid, but he must have been very charismatic to command huge crowds at public lectures,” says the Revd Dr Andrea Russell, Warden of Gladstone’s Library situated at the top of the high street.

The UK’s only Prime Ministerial Library was founded in the late 19th century as a memorial to Gladstone’s vision as a place “for the pursuit of divine learning”.

An elderly Gladstone is said to have delivered his books to the original building by wheelbarrow, aided only by a manservant.

The pin-drop-quiet Reading Room, dating from 1902, still has a collection of his personal volumes, the pages annotated furiously with his notes.

“I was a Disraeli fan but, since moving here, I’ve come to respect Gladstone’s vision for educational reform,” adds Revd Andrea, “as a man ahead of his time.”

Castle ruins

Back at the West End, we settle down for an evening of vintage vinyl and book browsing before an open fire, breaking off occasionally to look more closely at the artworks, notably Chris Levine’s Stoned, a Stonehenge standing stone glinting with diamond dust in the hallway.

Morning reveals another attraction: the ruins of the 13th-century Marcher castle in the grounds. It’s still privately owned by the family and best enjoyed from a bay-window seat with coffee and sourdough toast.

Gladstone died in 1898 and buried in Westminster Abbey but his heart remained in North Wales with his books and penchant for amateur forestry.

A winter-warmer break at the family home could be the ultimate romantic gesture for Valentine’s Day, or maybe inspire some Victorian-values thinking.

Either way, we came away from a weekend of reading, unwinding and logs on the fire having glimpsed something new — a wry smile on the lips of the ‘Grand Old Man’ in the faded photographs.

More from www.hawardenestateholidays.co.uk.

- Liked this? Try also How to spend a winter-warmer weekend in Wrexham

- Sign up to my newsletter for more about forthcoming articles, tours and writing workshops