I took my father away on holiday recently.

I thought a week cruising Norwegian fjords would do us both good and help us reconnect the father-son bond often lost amid the frenetic routine of our spin-cycle lives.

But, over the week, I realised something to my alarm: I feel my dad is drifting away.

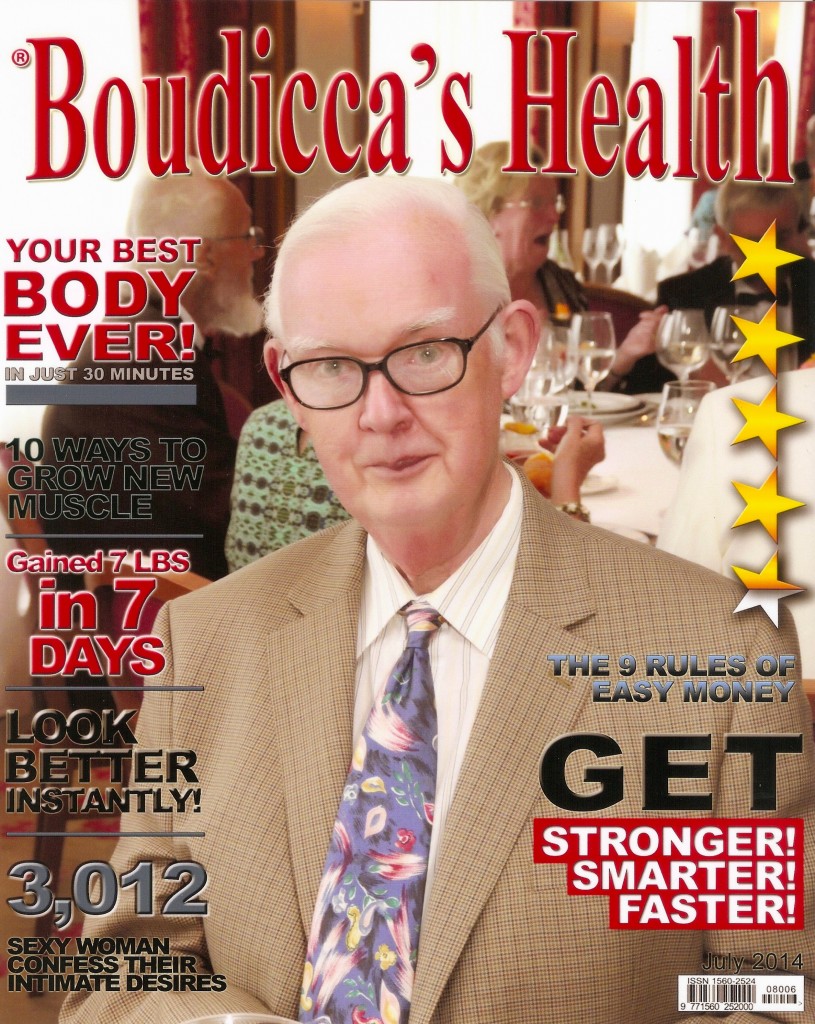

Christopher [pictured above] recently turned 75 and is going increasingly deaf. He is slowing down yet his physical health remains generally good. But, while was never a man of many words, he now seems increasingly withdrawn into himself, sometimes lost in a world of silence.

It’s a very different experience to my mother’s premature decline, taken from us by cancer aged just 67 after several years of debilitating illness.

The changes I’m now witnessing with my father are slower and more about his interaction with the outside world, rather than any physical ailment.

Is the deafness, or loneliness after losing my mother after some 40 years of marriage? He doesn’t seem unhappy or depressed. But, then again, he probably wouldn’t tell me if he was.

I wanted to understand – not just how to help him but also how to deal with the increasing sense of loneliness I feel.

I’ve already lost one parent and now the remaining one is physically present yet emotionally withdrawn.

There are now 11m people aged 65 or over in the UK according to recent figures from Age UK, the country’s largest charity dedicated to making the most of later life. That number is expected to pass 20m by 2030.

Some 36 per cent of all people aged over 65 currently live alone and 17 per cent report less than weekly contact with family, friends and neighbours.

“Subjective responses to our surveys suggest that feelings of loneliness, isolation and withdrawal are growing, especially amongst older men,” says Mervyn Kohler, External Affairs Advisor for Age UK.

“While women have a greater propensity to keep in touch with friends and neighbours, men coming off the back of 40 years of working life often find it harder to adapt to the pace.”

Age UK traces a linear connection between isolation and deteriorating mental health. The organisation campaigns to find more imaginative ways to spark the interests of older people – especially older men.

A recent success was the Men in Sheds scheme, a pilot project in three locations around the UK to bring older men together to share and learn new skills, such as woodworking. The project has now finished at a national level but some partners still run it at a local level.

“It’s a question of self value to your family and community. Without that sense of worth, it’s a very corrosive journey,” adds Mervyn.

“The way our population is ageing is a wake-up call to find new ways forward, engaging a generation no longer prepared to just put on its cardigan and slippers.”

Independent Age, the charity acting as a voice for older people with 1,500 volunteers across the UK and Ireland, produces a series of Wise Guides, offering practical advice for older people and their families. These are free to order or download from their website.

They also operate a freephone national helpline – 800 3196789 – and offer a befriending service by phone or to the home.

“How to help depends every much on the individual situation and what they want, especially after potentially major life events, such as bereavement or health problems,” says Rosie Collingbourne, Advice Manager at Independent Age.

Practical steps the charity offers include a benefits check, getting support from social services for care needs, equipment for around the home and access to day centres to meet other people.

In an age of families living further apart and people relying increasingly on digital communication, their volunteers talk to the person to assess their particular needs.

“We offer concerned family members the same kind of advice,” adds Rosie. “Often they want to take control but you can’t get a resolution for an older person. You have to work with them.”

My father is not completely withdrawn – far from it. He still does his own shopping, volunteers at a local National Trust property and regularly phones his sister in Australia. We live close by and he regularly spends time with his granddaughters.

But I’m worried. It was little things on our holiday that rang alarm bells for me – from deliberately leaving behind his hearing aid to a general reluctance to join in activities with other people on the ship.

The fjords were beautiful and the cruise relaxing but I also set sail for home resolved to act.

It’s time to seek help, not let him drift away.

* Do you have a similar experience of caring for ageing parents? Share your view and advice below.

Gazetteer