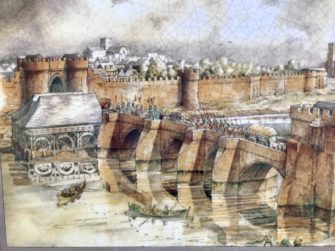

‘Here is a noble, stone bridge over the Dee, very high and strong built’ – Daniel Dafoe on a visit to Chester circa 1724.

It’s salmon season on the River Dee.

You can tell because the herons are out in force, queueing up on the weir like a a bunch of socially distanced shoppers outside Aldi.

The salmon, meanwhile, are taunting them, turning somersaults like Eastern European gymnasts as they swim upstream.

This Springwatch-style phenomenon is an event I’ve been observing recently on my daily exercise under lockdown.

The prime viewing platform is the Old Dee Bridge. This was historically the main entrance to the city from the Welsh side of the river.

It remains my gateway to city centre, the bridge that normally leads me to an event at Storyhouse, or the rendezvous-vous for an evening ghost tour.

We know from historical documents that the bridge was built around 1387, leading from the Bridge Gate on the city walls to an outer gate on the Handbridge side of the river.

The salmon swim upstream along the 11th-century weir alongside which is an area known as the King’s Pool.

Historically anglers would have to pay a fee to fish here, reflecting the importance of the Dee for salmon fishing.

The Abbot of Chester and his monks, meanwhile, had free access to this prime fishing spot.

Salmon fishing remains an important part of life on the Dee to this day with the hub of activity centred on an unassuming brick building known as the Chester Weir fish trap.

It’s here the salmon-fishing cognoscenti control the flow of the river to measure the number of salmon making their prodigal return to Chester.

The salmon’s return ebbs and flows, much like the waters of its host river, leading to the breeding season each autumn.

But I take comfort from the fact that, while global events evolve, some things endure.

As always, the herons know best.