* This is the fifth post in a new weekly series, highlighting stories from my travel-writing archive – many with no link online. I’m running them here in full. Subscribe to posts at this website for more.

On a quiet afternoon in Derry The Playhouse theatre still buzzes with activity. The writers’ group has just hit on the punchline, the art class revels in a riot of colour. I poke my nose into a movement workshop, led by the Colombian choreographer Hector Aristizábal, to find young dancers throwing sensuous shadows as early-spring sunlight streams in through the windows.

The theatre will play a powerhouse role as Derry steps into the spotlight this spring as the inaugural UK City of Culture. For Derry, the erstwhile heartland of The Troubles, the social and political conflict that blighted Northern Ireland for 30 years, it will be transformational. No wonder Derry was named by travel publisher Lonely Planet as the fourth most exciting city to visit this year.

“The arts always flourish in times of conflict,” says the fast-talking Playhouse chief executive Niall McCaughan, sprawling on a backstage sofa while a band tunes up for tonight’s show. “Derry nurtured strong connections to the arts via its community projects and now it’s time has come.”

I started taking the pulse of Derry’s renaissance earlier that day by crossing the Peace Bridge, the new link from the city centre to the Ebrington regeneration district on the far side of the River Foyle. Some of the cornerstone City of Culture events will be staged around this new public square, including the London Symphony Orchestra in March and the Turner Prize in October.

Over a lunch of dressed crab, spring lamb and slow-cooked pork at Browns, the contemporary-chic restaurant just across from Ebrington, head chef Ian Orr tells me about bringing local, seasonal produce to Derry tastebuds. “Derry didn’t have a strong food culture,” he says. “When I moved back here, I wanted to be the first.”

Orr was recently named Irish Chef of the Year at the Georgina Campbell Awards and plans to open a new sister restaurant, Browns in Town, across the Peace Bridge in the spring.

I spend the rest of the day taking in some of the other new arts spaces around the city. I find the young ensemble of the Echo Echo Dance Company rehearsing for one of their City of Culture commissions, Without, at a new studio, reviving a dilapidated old building on the ancient city walls. Their enthusiasm is almost tangible and I have to stop to catch my breath afterwards at the funky Café del Mondo in the Craft Village.

On the fringe of the Bogside district, past political-sloganeering murals and urban-industrial architecture, the Void Gallery is housed in one of the old shirt-making factories. “Many artists are returning to the city after years away,” says gallery manager Maolíosa Boyle, hanging her battered biker jacket on the stark-white wall of the minimalist space.

One of the gallery’s City of Culture projects is Artists Gardens, taking contemporary art out of the gallery and into the city. “I love the way art reflects the times,” she adds. “It touches all our lives.”

The next day I drive onto Belfast, cruising through the spring-stirring glens of County Antrim. I start by exploring the new Titanic Quarter, the sprawling regeneration area on the east bank of the River Lagan dominated by the newly opened Titanic Belfast (pictures above). The building with its four angular hulls traces the story of the world ‘s greatest shipping disaster across ten interactive galleries from Belfast’s industrial heyday to the post-disaster enquiry.

But it’s the Cathedral Quarter across the Lagan that has come to epitomise the vibrant new face of Belfast. From my base at the Merchant Hotel, the former Ulster Bank building reborn as the city’s grandest hotel, I set out to sample the vibe. The rabbit warren of streets clustered around St Anne’s Cathedral is alive with cafes, galleries and venues.

It has even spawned its own annual arts festival, the Cathedral Quarter Festival, staged each May.

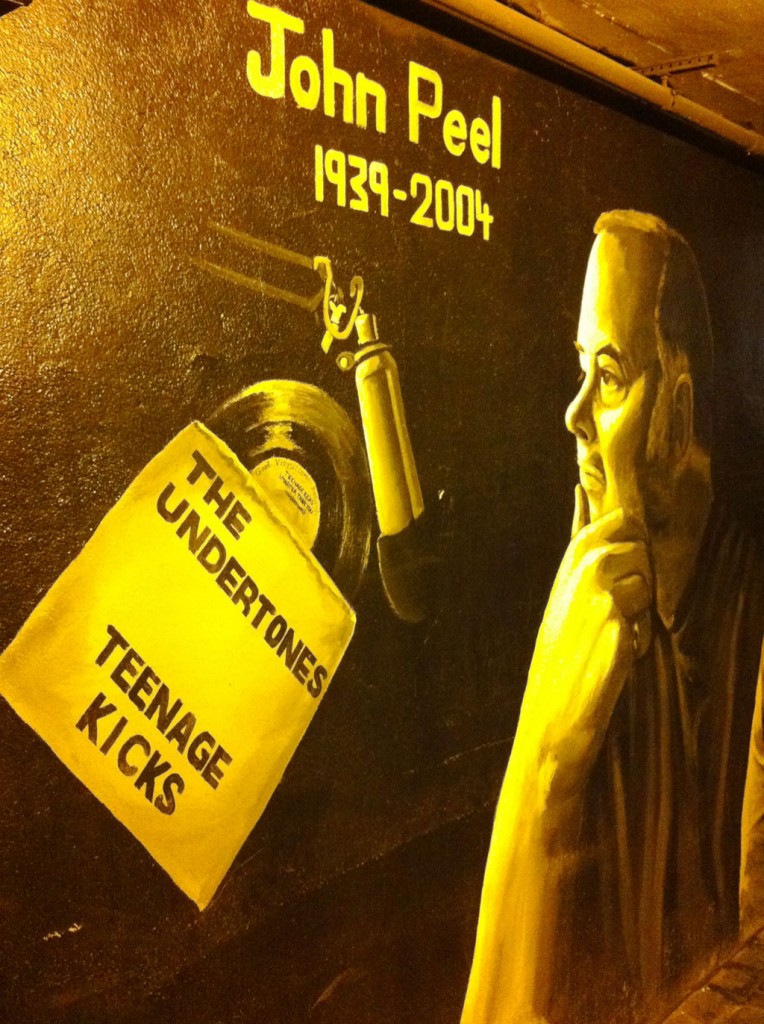

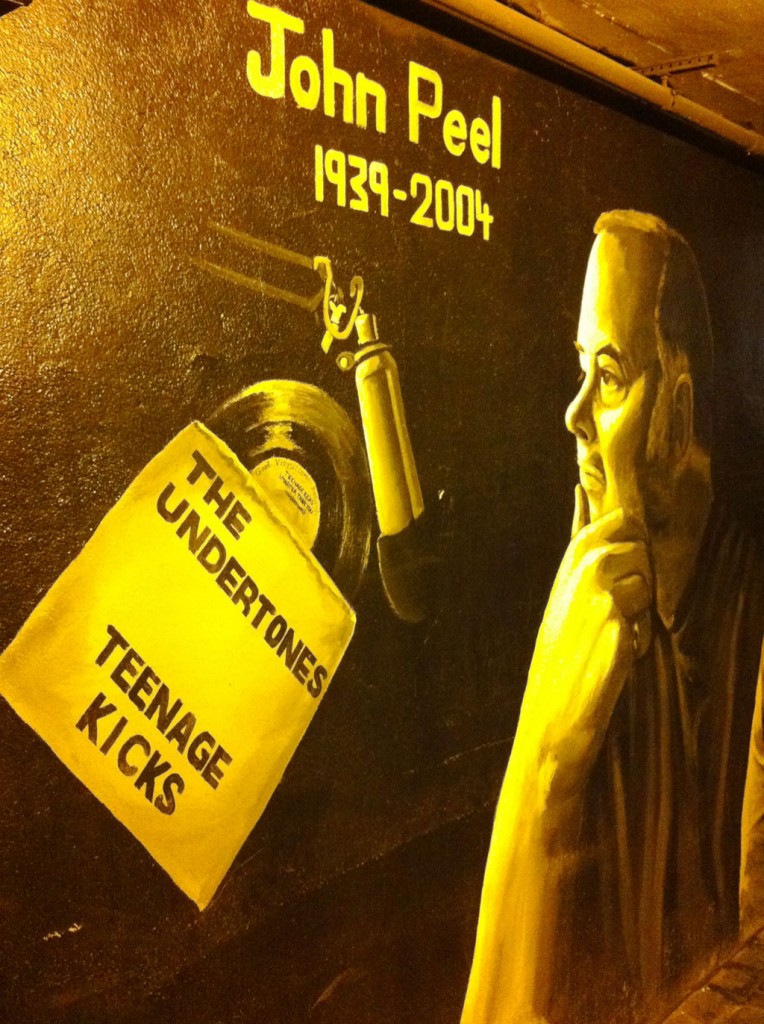

I follow the ancient passageways, nodding to murals to John Peel and Van Morrison, pivot past the Harp bar on Commercial Court, home of Belfast’s sparky punk-rock scene, and skirt the facades of old whiskey warehouses. The strum of power chords lures me towards the O Yeah Music Centre.

The centre’s fast-talking chief executive Stuart Bailie shows me round the collection of memorabilia from Stiff Little Fingers to Snow Patrol. The graffiti-scrawled rehearsal space upstairs smells of musty damp, flat beer and the hopes of next-generation Belfast musicians. He says:

“I was 17 and ripe for rescue when punk broke in Belfast in early 1978.”

“That spirit has energised us ever since and lives on in the Belfast swagger.”

Stuart introduces me to singer-songwriter Katie Richardson, frontwoman of Katie & the Carnival. She’s playing a low-key acoustic session that night at creative arts venue the MAC. I promise to be there.

That night before the show Katie tells me about Belfast’s creative impetus over a glass of red wine in the MAC bar. “When I was growing up, all I wanted to do is leave. But now,” she says before taking the stage, hunched over her guitar with pink-streaked hair and gold-lame platform shoes, “there are so many fresh ideas that we’re a long way off being mainstream.”

The next day I meet writer Glen Patterson for one last, heading-home pint of chocolate stout at the John Hewitt pub. Named after the Belfast socialist poet, the pub stages literary salons and Patterson is a regular, one of the resonant new voices in Northern Ireland’s rich literary tradition.

He recently co-wrote the script for Good Vibrations, the film about the Belfast punk scene, which opened at last year’s London Film Festival.

“Ten years ago the Cathedral Quarter was a no man’s land yet it’s steeped in nostalgia,” says Patterson, a Bradley Wiggins lookalike with a dash of Paul Weller mod. “My uncle ran a warehouse behind the John Hewitt and we’re sat within spitting distance of where The Undertones recorded Teenage Kicks.”

He finishes his pint. “Belfast embodies the fact there’s no last word in cities, only the latest. We’re not there yet,” he smiles. “But we are here.”

* This story is the most recent in a series about Northern Ireland; see also Post Conflict Tourism in Northern Ireland in travel writing and Northern Ireland campaign for the Daily Telegraph in copywriting. It was published in the March 2013 issue of Zoom Zoom magazine.