A wintery Friday afternoon and Ashley Jackson is holding court.

In the upstairs office above his West Yorkshire gallery, the 68-year-old, Barnsley-born landscape artist is nursing a crystal tumbler of well-aged single malt.

In the background an array of photographs show him receiving his courtiers: Sarah Ferguson, Rudolf Giuliani and professional Yorkshireman Fred Trueman.

“The quarry and mill men started the creative tradition of Holmfirth,” he chuckles to himself.

“The town had poets, musicians and intellectuals long before Last of the Summer Wine arrived. I had a gallery in Holmfirth for many years BC – before Compo.”

According to Ashley, Homfirth’s appeal is simply its visceral beauty – and the people inspired by it.

“Holmfirth is masculine country. If you appreciate the moors and nature, you’re welcome in Holmfirth with open arms,” he winks. “But the moors breed a certain type of person. They don’t breed bankers, that’s for sure.”

Coach parties

Ashley has granted me an audience to help me discover why this small West Yorkshire community is booming with house buyers chasing the life-work-balance dream.

To the outsider, the proposition seems unfathomable with dark, satanic mills looming over rough, forbidding moorland.

To the coach parties that clog up the triumvirate of main streets each weekend, the unique draw is the long-running television series Last of the Summer Wine, which first started filming in the area in 1972.

But to the converts, Holmfirth is a burgeoning arts hub with the Picturedrome Cinema, a glorious arthouse institution dating from 1912, the trail-blazing CragRats Theatre and a slew of well-regarded art galleries.

Ashley is right too – there was life before Compo. Bamforth & Co a publishing, film and illustration company based in Holmfirth, not only pioneered the saucy seaside postcard, but also preceded Hollywood as a film-making centre, making its first monochrome films in 1898.

Well connected

Located ten miles south of Huddersfield, Holmfirth is the main settlement in the Holme Valley.

A mill town since the Industrial Revolution, it’s overflowing with bucolic charm – think local stone-built cottages perched precariously on steep, twisting roads.

It’s also very centrally located for commuting to Sheffield, Leeds and Manchester, all university towns, and all within one hour’s drive. Within 20 minutes you can be cruising down the M1 or M62.

Despite the rural location, house prices are well above the district average and there is a high demand area for housing, while 11.3 per cent of economically active locals are self-employed compared to a national average of 8.3 per cent, according to figures from Kirklees Council.

“Holmfirth is small enough to feel friendly but big enough to be worth coming to.”

“It’s come of age as a destination with the advent of broadband,” says Max Earnshaw, Managing Director, EarnshawKay estate agents.

The broad range of housing stock ranges from a farmhouse with 30 acres for £1m to a two-bed cottage for £125,000, while a typical, four-bedroom detached house with a garden sells for around £250,000.

Particularly popular for conversions are the three-storey weavers’ cottages, as are the outlying villages of the Holme Valley, such as Upperthong, Netherthong and Wooldale.

“We get quite a young clientele – typically people in their early thirties who have done their time in London. People who want to retire head for North Yorkshire,” says Earnshaw.

“We have mill conversions with aspects of new build, but they cost £200,000 plus, so there’s not much for first-time buyers. But there are lots of empty old mills, which are ideal for setting up a business,” he adds.

Time for tea

Sue and Chris Gardener moved to Holmfirth seven years ago from Harpenden and did just that.

They bought the Wrinkled Stocking Tea Room, part of the building used as the film location for Nora Batty’s cottage in Last of the Summer Wine, as a going concern.

Downstairs an exhibition of memorabilia marks the 25th anniversary of the programme. But, as outsiders to Yorkshire, they are known as ‘comer-inners’ in the local parlance.

“We weren’t fans of the show. I always took the theme music as my cue to leave the room on a Sunday evening,” says Sue, as we sit amid floral tablecloths and china cups with an array of mouth-watering homemade cakes on the heaving sideboard.

“It’s okay as a comer-inner. People are genuinely warm and friendly. They may take a while to get to know but, when you do, you have a friend for life,” explains Chris. “And the countryside is stunning.”

“We walk the dogs every day and love the space. In Harpenden, we used to queue just to get into the car park at Waitrose.”

Cultural life

The Last of the Summer Wine set still draws the crowds but, in recent years, it’s the town’s cultural scene that has really captured the imagination – leading to a new influx of comer-inners. The HD9 postcode is now the second-highest theatre going audience in the region.

CragRats, a theatre, communication and education business, founded in 1991 and housed in a converted woolen mill at the edge of town, is the best exponent of the thriving arts community.

The company employs 80 staff and has over 300 actors on its books, running training programmes for companies as diverse as Diageo and West Yorkshire Police. The sprawling labyrinthine building is home to a theatre, a multi-media department and a corporate training facility.

“People think Holmfirth is the back of beyond but there’s a lot of raw talent in this area,” says David Bradley, Chairman of CragRats and co-founder of the business.

“The arts scene started with the film industry and I think the sense of creativity has been built into the fabric of the area ever since.”

“We chose Holmfirth for the building, the location and as a geographical centre as it’s close to Manchester and Leeds,” he adds.

“Most of all, I wanted to live somewhere that has a strong sense of identity and community.”

Your round

Back at the Ashley Jackson gallery, we’re draining our whiskies and bracing ourselves for the icy bite of winter.

“People round here tell it straight and I enjoy their directness. It comes from the moors. But go into any pub in Holmfirth and you’ll soon find out if you’ve been accepted,” chuckles Ashley.

The secret? “It’s the greatest gift you can give a Yorkshireman,” he winks.

“You know they’ve accepted you when they ask you to get a round in.”

What did you think of this story? Post your comments below.

This article was first published in the Weekend FT in 2008.

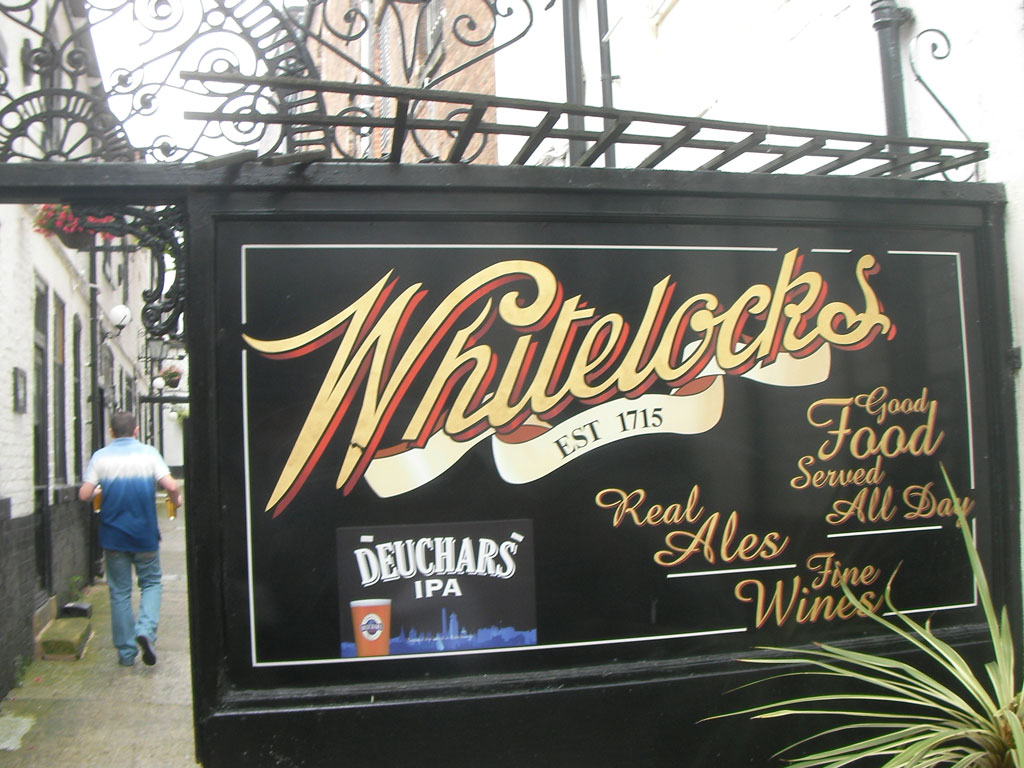

Liked this? Try also A memory-lane trip to Leeds.