It looks like an own goal for Liverpool — not Klopp’s team facing the wrath of The Kop but the announcement by Unesco that it could strip Liverpool of its World Heritage status.

The port city of Liverpool is currently one of 32 Unesco World Heritage sites in the UK. The area stretching along the city’s historic waterfront and onto St George’s Hall was granted World Heritage status in 2004.

Yet controversy has raged in recent years about a series of dockland developments, leading to Liverpool being placed “at risk” by Unesco in 2012.

The heritage body this week expressed further concerns about the Liverpool Waters regeneration scheme and plans for the new Everton football stadium in a former dockland site, citing the developments had resulted in

“serious deterioration and irreversible loss of attributes”.

The City Council hit back, saying some £1.5bn had been invested in upgrading Liverpool’s heritage assets.

Living city

The delisting would be a blow to the city, of course.

Post-industrial Liverpool has reinvented itself as a city of tourism, culture, and nightlife. Some 37m visitor arrivals each year contribute to an annual economic impact of £3.3bn for the city, according to pre-Covid figures from Marketing Liverpool.

The Covid-battered cruise industry has just set sail again with around 80 cruise calls planned this year, including Anthem of the Seas amongst other.

Liverpool has a proud maritime history, serving as a global port during the Industrial Revolution and a hub for transatlantic crossings at the turn of the 20th century. The city boasts 27 Grade I-listed buildings and is touchstone for Britain’s seafaring story.

In 1912, the Titanic disaster was even announced to the world from the balcony of what is now room 22 at the Signature Hotel, the former headquarters of the White Star Line company.

Laura Pye, Director of National Museums Liverpool, says the Unesco debate is more nuanced than a simple heritage-versus-regeneration trade off.

“We want future generations to learn about the city’s maritime heritage, of course, but Liverpool is a living, breathing city. It’s about finding new ways,” she says, “of using heritage to evolve.”

So, can sites survive a delisting? Two places so far met that fate: the Arabian Oryx Sanctuary in Oman and the Dresden Elbe Valley in Germany.

There are currently 53 locations on its heritage danger list, including the Bolivian city of Potosi and the Everglades National Park in the United States.

Unesco also warned that Stonehenge could be added to the danger list at its 2022 review if plans to reroute the A303 road in Wiltshire are not modified. Yet, Covid aside, these destinations continue to draw visitors.

Moreover, Liverpool has an innate ability to rise phoenix-like from the ashes.

As a teenager, growing up in the Northwest of England, I saw Liverpool through the wilderness years of the Eighties, bowed and monochrome.

I also witnessed the green shoots of recovery when the International Garden Festival converted a former household tip into the UK’s first ever garden festival in 1984.

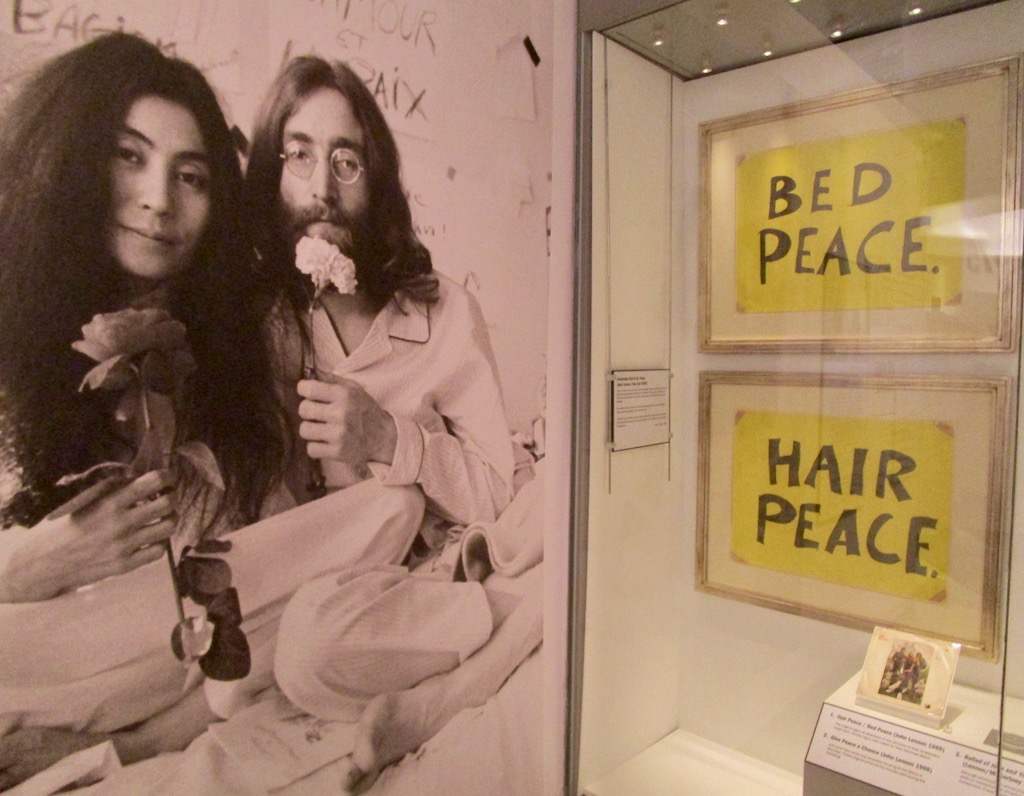

And I watched from the crowd gathered in front of St Georges Hall as the former Beatle, Ringo Starr, played live on the roof to launch Liverpool’s transformative tenure as the European Capital of Culture in 2008.

I find the city reborn these days. Tate Liverpool will host a summer-blockbuster Lucian Freud exhibition from July 24, hotels are relentlessly booked out for Premiership home games for both city teams and Bold Street bars are buzzing again with post-pandemic revellers.

Liverpool has some fight in her yet.

Seeking solutions

There’s one month left to reach a compromise before the final decision. Joanne Anderson, Liverpool’s newly elected mayor, says heritage and regeneration are not mutually exclusive and has invited Unesco to see the developments first-hand. She wrote on Twitter:

The report recommending deletion of Liverpool’s World Heritage status will take time to digest, as its quite detailed.

A full response will be made via the @DCMS but our position is clear – we will be asking the committee to defer & review our case over the next 12 months. https://t.co/Vmj0TlzeDe— Joanne Anderson (@MayorLpool) June 21, 2021

So, can Liverpool salvage its status as a maritime-heritage hub?

I hope so. It would be a shame for cruise arrivals, disembarking from the Cruise Terminal on the waterfront this July, to find that their gentle stroll through Liverpool’s Mersey-docked history, walking from the Three Graces to the Merseyside Maritime Museum in the Albert Dock, no longer gets the Unesco nod.

But I’m sure that Liverpool would rise again.

As Peter Colyer, Chair of the Liverpool City Region Tourist Guides Association, told me:

“Liverpool moves onwards and upwards. We would be saddened but the loss of status, but it would not impact significantly on visitor numbers.”

“The regeneration of Liverpool,” he added, “is an ongoing work in progress.”

So Unesco be damned. As any football fan knows, Liverpool may go one down at home sometimes — but they always fight back.

Read the edited story at Telegrpah Travel.