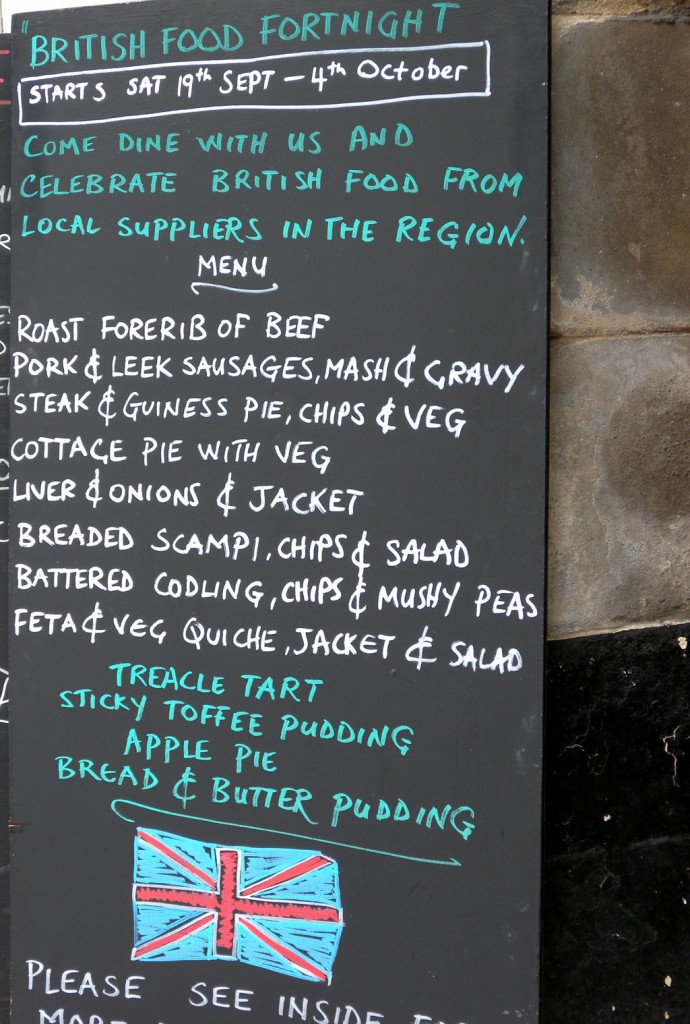

* British Food Fortnight runs until October 6 this year, celebrating local produce and regional flavours. Some of my favourites come from Cumbria and this story picks up on that theme.

Follow me on Twitter or subscribe to the RSS for more story updates.

Alex Brodie sups his pint and ponders for a moment.

“Do drinkers become journalists, or journalists become drinkers?” muses the former BBC World Service broadcaster turned microbrewer.

Reclining in his beer hall-style tasting room in his Cumbrian craft brewery, he sups a pint of the award-winning Hawkshead Bitter and lets the question roll around the high ceilings.

I join him on the leather sofas with a pint of dark and malty Brodie’s Prime and a piece of Welsh rarebit from the next-door café, Wilf’s, and quaff my beer appreciatively. “I love beer,” Alex stirs from his reverie.

“A good beer on a hot, sunny day is pure Ambrosia.”

“Walking the hills and sitting in country pubs sustained me through years of reporting from the Middle East,” he adds.

Real ale trail

Cumbria has a rich heritage of artisan brewing [pictured above] since the 1830 Beer Act first gave rise to a proliferation of local brew houses.

By the 1970s real ale was dying out but, thanks to Gordon Brown’s 2002 budget, whereby the excise duty was cut by 50% for brewers at a certain level of production, there are now over 600 independent breweries in the UK, of which 20-odd are based in Cumbria.

The Hawkshead Brewery, having relocated to the picture-postcard village of Staveley in 2006, is one of the new breed.

The brewery currently produces 80 brewers’ barrels per week [4 x 9-gallon casks] and sells its four permanent beers, plus seasonal beers, to 170 UK pubs. There are plans afoot to expand brewery tours to offer short courses for amateur would-be brew masters.

“We’re doing our best to change the image of real ale. We now stage two beer festivals per year and it’s not all beards and bellies — about half the drinkers are female,” enthuses Alex.

“There are now lots of microbreweries playing around with hops to produce fruity, hoppy beers,” he adds. “In same way new-world wine producers took the fear away from wine by talking about the grape, we’re now talking about hops.”

I’ve come to Cumbria to test drive the Lakes Line Real Ale Trail, a green-friendly initiative collaboratively launched by Westmorland CAMRA and the Lakes Lines Community Rail Partnership, plus First TransPennine Express.

The trail is based along the Lakes Line, a rural branch line that trundles through the scenic countryside of the Lake District National Park from the mainline train hub of Oxenholme to Windermere.

“We were conscious of the impact of the 16m visitors to Cumbria each year. This seemed an obvious way to showcase our local breweries while supporting sustainable travel and encouraging sensible drinking,” says Chris Holland, Chairman of the Westmorland branch of CAMRA.

“It’s only seven miles of railway now, but we plan to expand the idea to other parts of the region’s rail and bus network.”

Local brews

On a bright Lakeland morning I set out from my base at the Riverside Hotel in Kendal, a traditional inn serving a decent pint of Lakeland Gold, to explore the hop-flavoured trail.

There are nine pubs along the route, all within a short walk of the stations, and some attached to specialist small breweries.

Each has their own appeal from a swift lunchtime half of Directors in the Lamplighter Bar in Windermere, followed by a hike by the lake, to a mid-afternoon pint of Blond Witch at the Station Inn, Oxenholme, while soaking up the view and waiting for the next train.

It’s a greener way to sample the perfect combination of Lakeland beer and scenery, while supporting local transport.

Some of the nine establishments offer discounts upon presentation of a valid rail ticket, but make sure to have a copy of the timetable to hand at all times.

After developing a taste for Ulverston Pale Ale at the Eagle and Child Hotel in Staveley, it’s easy to roll out onto the station platform to face a sobering 60-minute wait for the next train.

Award winner

Towards the end of the day, as the sun hangs heavier in the sky than a Lakeland downpour, I head for my last stop, the Watermill Inn and Brewery.

Located down in a country lane in the village of Ings, outside Staveley, the cottage-industry microbrewery was founded in 2006 as an add-on to the family pub.

The two-man operation now produces 22 brewers’ barrels per week — around 6,300 pints — and the seven-beer portfolio includes three main brews plus seasonal ales.

“Brewing is a craft, the product of good ingredients and good practice,” explains the softly spoken brewer Brian Coulthwaite as we sit on the outdoor terrace with a pint of Blackbeard Ale and views across the rolling, sheep-grazing fields to Windermere.

“It’s essentially chemistry, all formulas and calculations. What I enjoy is experimenting to create new flavours.”

Back at the Hawkshead Brewery, Alex is taking me on a whistle-stop tour of the brewery and threatening to treat me to sneak preview of his latest brew, a Damson-flavoured stout.

“There’s a perfect storm for this kind of trail now with the public keen on local produce and green issues,” says Alex, indicating the ‘copper’, the vat where hops are added to give the complexity and flavour of the beer.

“It gets people out of their cars and walking, or using a train line that is periodically under threat,” he adds.

“After all, this is a national park, not a car park.”

* This story was first published in the Daily Express in 2008. Liked this? Try Local Food Heroes in Cheshire.

And post your comments below.