* This story was published at the weekend in an edited form. Here’s the full version.

Follow me on Twitter, or subscribe to the RSS, for weekly updates from my travel-writing archive in the months to come.

It was the summer of 1993.

I left behind my life as an undergraduate at Leeds University and a cub reporter on the student newspaper to travel to a country most people had never of and live with a family I had never met before.

A summer of teaching English at a summer school and learning about a new culture lay ahead.

In Chisinau, the capital of Moldova, the summer air was heavy with the smell of wild flowers amongst the vines, the sound of dive-bombing mosquitoes and the outcry over the perestroika reforms unfolding before my eyes.

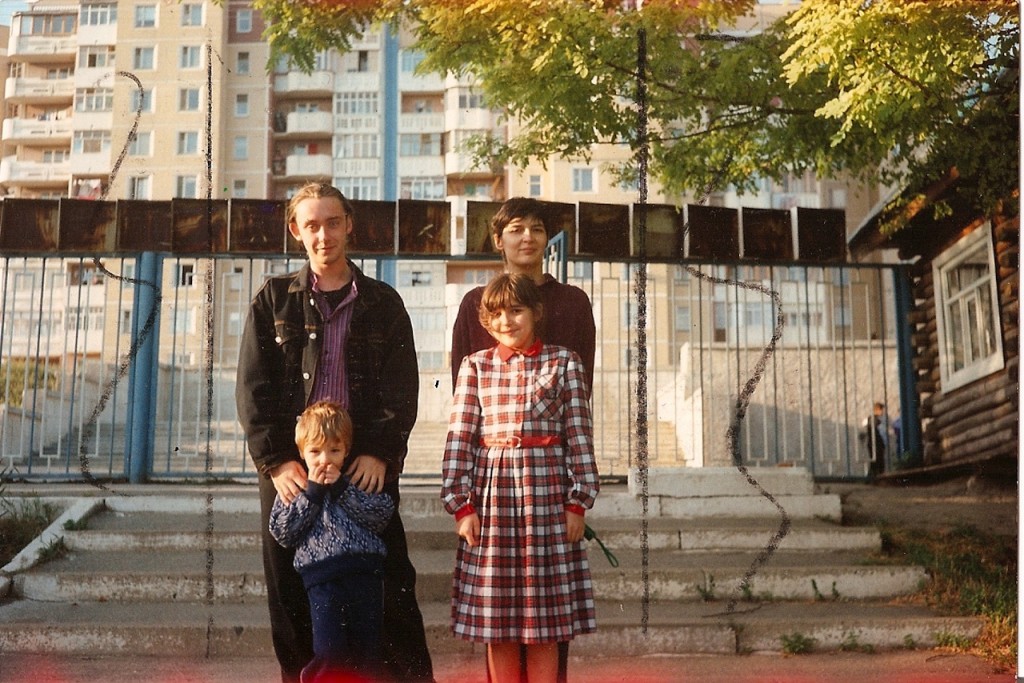

The Avdeev family [pictured above] took me into their simple Soviet-block home and treated me as their own.

Mother Natasha and father Sasha became surrogate parents while Tanya, then ten years old and the main English speaker in the family, and four-year-old Vova, were my adopted sister and brother.

I still remember joining Natasha in the bread queue only to find the shelves empty as we approached the front, trips to see the emaciated animals in the zoo with the children and long, hazy nights spent drinking absurdly cheap and surprisingly palatable red wine in the bar of the Soviet behemoth Hotel National.

I even kept a few snaps as a memento of my brush with Mother Russia.

After I went back to university in Leeds that September, I exchanged Christmas cards with the family. Letters followed as the years passed and then we lost touch. Life simply moved on.

Going home

Now, 15 years on, married with a child of my own, I’m back in Chisinau armed only with that clutch of old photographs and a well-thumbed letter with an address in the city’s Botanica suburb.

I’ve come to find my erstwhile host family and pose the question: what has changed more since 1993 – Moldova or me?

To find the answer I start my quest at the feet of the statue to national hero, Stefan cel Mare. The boulevard named in his honour, Chisinau’s answer to the Champs-Élysées, stretched out in front of me.

The city looks transformed at first appearances. I remembered empty shops, faded, grey-concrete facades and street-side kiosks selling glasses of cordial watered down with water of dubious prominence.

Chisinau has since seen an explosion of casinos, mobile phone stores and designer-brand boutiques. There is more Dolce and Gabbana on display on a Tuesday lunchtime along Stefan cel Mare than there is on the catwalks of Milan and Paris.

In 1993 I used to struggle to find a restaurant serving lunch during my break from classes. Today the pavement terrace of McDonald’s is packed with lunch breakers munching on burgers.

Across the road is the main post office, where I used to send telegrams back home to my concerned parents. Today the it is sandwiched between a well-stocked, 24-hour supermarket and an internet café.

But venture away from the main street and the scene is one I am more familiar with.

Two blocks north of Stefan cel Mare boulevard the roads are pitted with pot holes, wizened old woman with headscarves and tired eyes sweep dusty stairs and people from the outlaying villages hawk flowers, fruit and knick-knacks at makeshift market stalls pitched randomly on the street.

Before my departure via Vienna I had spent some time hunting around online and found both a guide and a homestay for a modest fee payable in Euros.

I didn’t know what to expect from the trip as my host met me from the airport and whisked me through the city in a battered taxi. I arrive at their home to find my base was to be an apartment block in the city’s well-serviced Riscani district, a 15-minute minibus ride to the centre of town.

For the next few days my bed was a mattress on the floor in the lounge and the facilities shared with English-speaking mother and daughter Larisa and Natasha.

As I tuck into a delicious home-cooked meal on the first night of polenta, salad and pork fried in egg white and breadcrumbs, preceded by a steaming bowl of Moldovan borsch, Larisa tells about how life in Moldova has changed since the early Nineties.

“For me 1993 was a good year,” she smiles, knocking back a glass of the remarkably good local red wine. “I had a good job with a good salary, even if there was nothing to spend the money on.”

“Now you need a salary of around 300 Euros per month to have a good life here, but many jobs pay less than 100 Euros.”

Family reunion

The next day I’m sitting in a taxi my stomach turning somersaults like a Russian gymnast with an intoxicating blend of nerves and excitement.

My host, Larisa, had looked up the address of the Avdeev family and found a phone number. By remarkable chance Natasha and Sasha are still living in the same apartment and, after a broken phone conversation blending Russian and English, they invited me over for lunch.

I later learnt they had borrowed produce from family and friends to prepare the spread of mashed potatoes, meatballs and salad they would lay on for my prodigal return.

I got out of the taxi and looked up at the apartment block, memories flooding back as I gingerly clutched the flowers and bottle of brandy I had brought as a gift. But, as the door of apartment 29 opened and I was welcomed with a multitude of hugs, the nerves evaporated.

I had come home.

After lunch, time to swap memories and a chance to show off photos of my own family, I asked the family about how their lives had changed since my last visit.

“Chisinau looks like a European city, and the prices are European prices, but the salary is still at Soviet levels,” explains 25-year-old Tanya [pictured below], now married and mother herself, bouncing three-year-old Nikolai on her knee.

“In Soviet times you needed friends to get things. Now everything is available but people don’t have money to buy.”

“More than 25 per cent of Moldovans are now working abroad in Israel, Turkey, Italy and Russia. When you go into the villages only the grandmothers and babies remain,” adds 20-year-old Vova [pictured below], who was in short trousers when I last saw him and is now studying physics at the local university.

“Everyone was equal in the Soviet times,” he says. “Now we have rich and poor but no middle class.”

City break

Over the next few days I spent time exploring the city, visiting some of the villages outside Chisinau and walking in the park with Tanya and Nikolai.

It was time to get to know each other all over again.

On the last night I asked mother Natasha about her vision of the next15 years in Moldova.

She thought for a moment and then said solemnly, via Tanya’s translation, “More cars and smaller parks as Moldovans come back from working abroad and buy plots of land to build new houses.”

“The ecology will be worse and water shortages more severe. But we’ll still here. This is our home.”

There are tears in my eyes as I head for the airport a few days later. I’m emotional to say goodbye all over again but my three-year-old little girl is missing me back home.

This time, however, I leave safe in the knowledge that there will always be a home from home waiting for me in Moldova with a family whose lives are now intrinsically intertwined with my own.

After 15 years and changing lives, we’ve both changed. But we’re both somehow still the same.

* This story was first published in The Guardian in August 2014 under the headline Nostalgia trip: A family reunion in Moldova.

Liked this? Try also Revisiting East Berlin after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Post your comments below.